Don’t trust your instincts: you’ll wake up in jail. – Andy Jerram. Ski Instructor to the rich & famous.

Sabermetrics, the search for objective knowledge about baseball by analysing statistical records, has transformed the sport. Its’ concepts are encapsulated in the Hollywood movie Moneyball starring Brad Pitt based on the book Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis.

Moneyball – the replacement of intuition with data

The central premise of Moneyball is that the collective and accumulated wisdom of baseball insiders including players, managers, coaches, and scouts is doomed to failure. It states that despite ample opportunity to refine their skills over years of practice, their selection of players turned out to be subjective, and often flawed. Moneyball advocates the replacement of intuition with data. Decisions should be based solely on evidence and reason. That is how you win. When the evidence points one way, and gut feeling points another, you go with the evidence, whether in baseball or in avalanche terrain.

In North American avalanche education we’ve been playing Moneyball for many years now, replacing intuition in an uncertain world with the absolutes of any and all data and information we can find. But is there still room for us to cultivate intuitive thinking? Should we be tapping into our gut feeling for assistance when it comes to complex, fast evolving high stress situations?

Your goal shouldn’t be to buy players. Your goal should be to buy wins. – Moneyball.

According to Kahneman in Thinking Fast and Slow, expert intuition is gained when three criteria are met:

- Repeated practice.

- Immediate feedback. You have to know at the time whether you got it right or wrong.

- Regular order in a high validity environment, such as in a game like chess.

Unless these three conditions are satisfied, expert intuition will be difficult to obtain. Here lies the rub: we seldom operate in a high-validity environment when we are dealing with the uncertainty and spatial variability of a winter mountain snowpack. Indeed, well trained backcountry users are likely to avoid the avalanche problem altogether by prudent use of the avalanche forecast. It is only when we engage with an avalanche problem that we begin to truly understand it. Only a subsection of backcountry users, such as forecasters and ski patrollers running mitigation, actively go out and seek avalanches on a regular basis, and even then, it is not uncommon for them to operate in a feedback vacuum. If Kahneman is correct then expert intuition has no business in our backcountry decision making. Indeed, research looking into the effectiveness of Sabermetrics shows that even when experts were given the baseline information of the statistics and then asked to add to it with their expertise and intuition, they actually performed worse than novices given the same data.

The Failure of intuition in Mountain Professionals

The inability for us to meet Kahneman’s three criteria for developing expert intuition whilst operating in the uncertainties of the backcountry is perhaps partly the reason why guides feature so heavily in avalanche involvements (1). They falsely believe that the process of repeated practice alone is meeting the criteria for gaining expert intuition, they are trying to develop expert intuition in a low validity environment without immediate feedback.

Avalanche training for mountain guides in Europe remains much less structured, formalized, or as in depth as that of their North American counterparts. The insular nature of the European mountain guiding profession, seldom operating in teams or working for guiding outfits, has newly qualified guides lacking the required mentorship to provide the nuanced feedback from the snowpack needed to cultivate intuition (2).

Kahneman also refers to fractionation of skill as another source of overconfidence. Professionals who have expertise in some tasks are sometimes called upon to make judgments in areas in which they have no real skill. Expert skiers with the skills to guide guests in a high mountain environment, and indeed have undergone a degree of avalanche training, are expected to make subtle judgments in areas in which many have no depth of expertise. Put bluntly, they’re not nearly as good as they have been told they are when placed in an avalanche environment.

So that’s it. Intuition has no place in the backcountry. It coerces mountain professionals into making poor decisions and we should continue to focus on honing a Moneyball mindset, checking our human behaviours, and seeking out data. Right? Well perhaps not…

Stewart-Patterson, an IFMGA mountain guide and professor at Thompson River University argues that ski guide training programs could and should incorporate intuition-based avalanche training in addition to the analytical training they currently receive. He noted that the ski guides in his study group regularly relied upon their intuition regardless of the level of their formalized avalanche training. It would therefore seem at odds not to train and develop that intuition. Our reluctance to teach intuition is likely due to the perceived difficulties involved in such a training process, fortunately Stewart-Patterson offers solutions; such as providing an opportunity for structured feedback from peers during p.m. guides meetings, extended periods of debriefed tail guiding and utilising low fidelity simulation training as used in other high-risk decision-making industries.

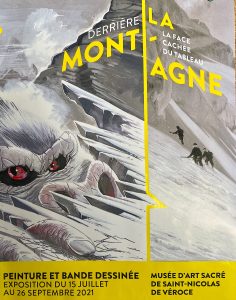

Mont Charvin

Intuition is a Warning – Ian McCammon

On New Year’s Eve 2019 four of us set out to ski from the summit of Mont Charvin, a popular one-day ski tour in the Aravis Range of mountains close to the Mont Blanc massif in France. Unglaciated and non-technical it’s a good early season objective. The Aravis Range is prone to glide avalanches throughout the season due to their slopes being steep and long grassed, providing an ideal sliding bed surface for the snowpack. On arrival at the bitterly cold trailhead we noted that our route of ascent had a hanging fish mouth of a glide crack threatening part of our up track on the final headwall, to which we’d be exposed to for an hour or so. We briefly commented on it then dismissed it. Temperatures were frigid in our pre-dawn start. As a strong fast team of four we’d be stripping skins on the summit by mid-morning before any warmth from the weak December sunshine could have any meaningful effect on the snowpack up high.

Three hours later and 50 meters directly beneath the giant fish mouth, we approached the safety of the summit ridge, the snow pack was indeed feeling completely locked up as we transitioned to ski crampons to tackle the steep hard snow of the headwall. I felt a small ‘pop’ beneath my ski’s. Not a whoomph, not a collapse, just a weird tiny little pop. A while later as the sun finally came onto the face I felt another similar pop – more distinctive this time. Glide avalanches are notoriously difficult to predict and offer little in the way of clues to their imminent detachment. We’d be through the danger zone within five minutes if we continued skinning up. A short but succinct discussion was initiated by one of the team:

I felt a really weird pop.

Huh! Yeah me too, I’ve felt it twice now.

Let’s get out of here. (it wasn’t a suggestion my ski partner was making, he was alarmed and already stripping his skins – fast!)

Umm…Okay!

Mount Charvin New Year’s Eve avalanche. Injured parties can be seen at mid height and at the base of the peak.

Suddenly gut feeling had our cortisol levels red lining. I recall thinking: ‘these guys think we’re nuts’ as a group approached us from the skin track below, watching us inexplicably transition and traverse away. Three minutes later and barely out of its path, a glide avalanched released full depth; playing pin ball with several groups ascending below us.

Back at the safety of a flat meadow beneath our peak, having checked on the walking wounded, we contemplated our decision making that day as the first of the PGHM rescue heli’s came into view. Was it my partners intuition that saved the day? Clearly a failure in our heuristic thinking had placed us in the line of fire, but did my Moneyball mindset keep me on the slope too long, waiting for additional information in order to complete my decision making process?

Human Factors are the baseline of all avalanche accidents. They are always decisions that went wrong. They are all situations that we have put ourselves into. Drew Hardesty

An intuition based decision model

As an industry that has bought in into the the Moneyball mindset complimented by a heuristics and biases view of how we should make our decisions, perhaps we have overlooked elements of an intuition mindset that have the potential to serve us well. We have failed to appreciate the value of other decision-making models which exist. The Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) model as championed by Gary Klein, unlike Kahneman, advocates using intuition as part of the natural process of how we arrive at a decision in real world situations. Interestingly for us, he observes it is of particular value to practitioners that operate in high-risk environments.

Scientists seek the truth. Practitioners search for survival

Klein looked at the decision-making process of certain groups in society, primarily risk practitioners. These groups had developed expertise in fast, high consequence uncertain environments. He examined how firefighters, fighter pilots, and police officers made their decisions. He concluded that these groups developed intuition that was worth trusting. His research can be seen to be particularly valuable in the avalanche realm as the study environment was based on those operating in the field, opposed to university based control groups often used in the experiments conducted into Heuristics and Biases.

Klein observed that first responders who operated in High Risk / High Frequency events developed what he described as Recognition Primed Decision Making (RPD). To his surprise the firefighters he studied weren’t interested in weighing up options to make their decisions as he had anticipated, but that they simply sought recognition of past similar situations that they had built up in their memory over years of experience. They would then pattern match their mental database to the task in front of them and then re-enact or adapt similar solutions that had worked for them previously.

The caveat being that this is a tool for experts. Only experts have gained sufficient experience in all aspects of their field to possess a rich repertoire of patterns in their memory, being able to make fine discriminations that may be invisible to others. They possess sophisticated mental models of how things work, even though they often cannot verbalize the rationale for their actions, and have resilience to adapt to complex and dynamic situations. These experts have developed their intuition as a tool.

An Intuitive decision style provides the ability to make quick high-quality decisions when time is short. If follows that it will work well when we are tired, cold and suffering from cognitive overload. In this respect Klein’s understanding of intuition overlaps with the concept of Kahneman’s system 1 thinking.

Compare this to an analytical decision style. Analytical thinkers want their decision-making process in the mountains to be like Chess, when in fact operating in the uncertainty of a winter snowpack is more akin to playing Poker. While both are games of skill, Chess has all the information required to win laid out in front of us: a Moneyball data rich environment. In contrast, Poker is full of hidden information where we are often putting the jigsaw together in the dark. The problem with those that are embedded in an analytical mindset is that we operate in an environment where availability of data is often scarce, spatially distributed and constantly changing. We need tools to address uncertainty and using intuition is a tool that can help us.

Recognition Primed Decision Making (RPD). A tool for survival and resilience.

As an avalanche practitioner I’m always looking for an edge wherever I can find one when setting up for a day in the mountains, usually in the form of a stack of small margins that I judiciously load up on for breakfast washed down with a big steaming mug of Moneyball data. If a Moneyball mindset gives us a baseline from which to make decisions in avalanche terrain, we can use this baseline to identify anomalies. After all, isn’t Intuition simply the subconscious noting the pattern being incorrect?

For expert practitioners, using intuition in high risk / high frequency situations is their default operating method. But it is their ability to recognize that they are in a high risk/ low frequency event that will get them off the slope when the Moneyball data says they’re still good to go, such as the weird little pops in the snowpack on Mont Charvin.

High risk / low frequency is the ‘404 – no results found’ page we get when searching for pattern recognition in our memory banks for previous similar situations. These previously unencountered anomalies in the patterns that we struggle to reconcile should be a red flag. It is in these high risk / low frequency encounters where bad decisions occur and outcomes are often catastrophic. Recognizing where we are located within our margins of safety gives us the opportunity to relocate ourselves in this space. Decision making expert Laura McGuire argues that this recognition of where we stand in relation toan acceptable threshold is true resilience.

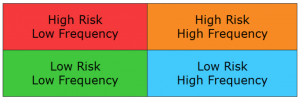

Image: Risk/ Frequency matrix – Gordon Graham

Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) – a pathway to Reflection

Steven Haines a Geneva based touch therapies specialist and author of a series of books on the interaction of body and mind attended a Rec Level 2 we ran in the mountains surrounding Chamonix last season. He offered the insight that we can train instinct by learning to value and pay attention to our feelings. Both feelings as sensations and feelings as emotions. ‘The former leads to the latter. Instinct becomes a skill to be developed’.

This isn’t as warm and fuzzy as it may sound. Haines added that he appreciated our invitation to the students to pause at key moments of their day, but from his perspective for reasons we hadn’t even considered. As avalanche educators we know that slowing down at key moments: transitions from the up track to the descent, preparing to drop into a consequential line or throwing a hand charge during a control line run, can provide a valuable pause to foster situational awareness and facilitate communication. Haines offered a refinement he valued; whilst in the pause to notice how present you are or how absent you feel. There’s a value to this form of self-grounding for making decisions from a good place. In essence, self-awareness is critical to effective situational awareness. Being centered improves our intuitive decision making.

Intuition tools

- Expert intuition is reliant on experience. In the low validity environment of avalanche terrain, it requires coaching and mentoring from skilled practitioners over an extended period to address the lack of timely feedback.

- We must be honest with our level of expertise. Mountain professionals with a handful of seasons under their belts lack the personal database to use intuition reliably.

- Use intuition as a one-way valve: use it to say no – never to say go.

- Value tapping into your feelings, both physical and mentaI during your day. Especially during a pause at key moments. Self-awareness facilitates better situational awareness.

- Anomalies are missing gaps in our personal database of knowledge where intuition has little value. Recognizing anomalies is a cue to relocate yourself within your set safety margin, they’re a warning to change your plan or back off.

It’s useful to demystify intuition. Experts who possess intuition are often perceived to have a shaman like aura. Both Klein & Kahneman agree that intuition is simply the recognition of patterns. Lynne Wolfe observes that intuition can be viewed not as a linear single thread of information along a timeline, but as stitches in a tapestry that we connect subconsciously to form a feeling in the background.

Whilst it may be difficult to gain expert intuition in the low validity environment of the mountains, once obtained it can be a powerful tool in addressing uncertainty and can complement a heuristics and biases mindset. Intuition and analytical models are not mutually exclusive events or processes. The blending of a human factors and Naturalistic Decision Making will always be a better strategy than relying solely on a Moneyball mindset.

References

(1) In Switzerland over a five-year period to 31 March 2006, 18% of victims were guided. This figure has remained steady over the subsequent 15 years- Source SLF. In France 14% of avalanche deaths over a 20-year period included a mountain professional in the group – Source ENSA.

(2) (Fadde & Klein 2010)

Moneyball: It’s Intuition vs. Evidence – David Johnson.

A naturalistic decision making perspective on studying intuitive decision making – Gary Klein

Conditions for Intuitive Expertise – Kahneman & Klein

Think with Pinker BBC Podcast – Nov 18 – 2021 Think Twice

Thinking in Bets – Annie Duke

High risk, low frequency lecture YouTube – Gordon Graham

Hindsight 20/40 – Drew Hardisty

that is a really good summary which is tough to do with such an esoteric topic. I really can’t add much other than to stress what Kahneman had to say about “Stock pickers” which i think is a perfect analogy to “slope pickers” for all the reasons you cover, especially the absence of feedback.

I think its useful to delineate the miss conception of what a “avalanche expert” is commonly percieved as ( avalanche forecaster), from what they actually are – a risk manager. Like the stock picker we are only fooling ourselves if we get the idea we can reliably say which slope will avalanche or not, just as a stock picker deludes themselves selecting individual stocks in anticipation of high performance or a dive. There is only enough information available for creating a projection, not a prediction, and then only generalized over similar terrain features under similar snowpack and weather conditions. That is so ambiguous you always must manage your assets exactly as an astute investor will – what happens if I’m wrong.

We really can’t become authentically expert at predicting avalanches, no more than a seasoned stock picker can reliably pick a stock. But we can become expert risk managers because for risk management behaviours, there are adequate feedbacks to nurture good reliable intuitions for those sort of broad scale observations.

Excellent article for all of the reasons noted above. I also appreciate the demystification of intuition and the suggestions for fostering it, even if it will never be 100% reliable. As a teacher in the mountains, I see all of the behaviors that I’ve managed to survive, endless enthusiasm, singled minded focus on the objective, and something that hasn’t been mentioned in this article, physical exhaustion. I now have enough years of data (and on some days fitness) to look back and observe that o make worse decisions when I’m tired or scrambling to keep up with a stronger group. The advice to plan on observing (feeling) and communicating at key transitions is a teachable habit. It’s also a group agreement that can be established (“can we agree to pause here, here, and here… maybe here of needed…?”) . For me this described my screening test for mountain partners, my life will be long and I can build an extra 20 minutes I to my day to eat chocolate and survey the ever changing and beautiful mountain environment.

Thank you for the article!